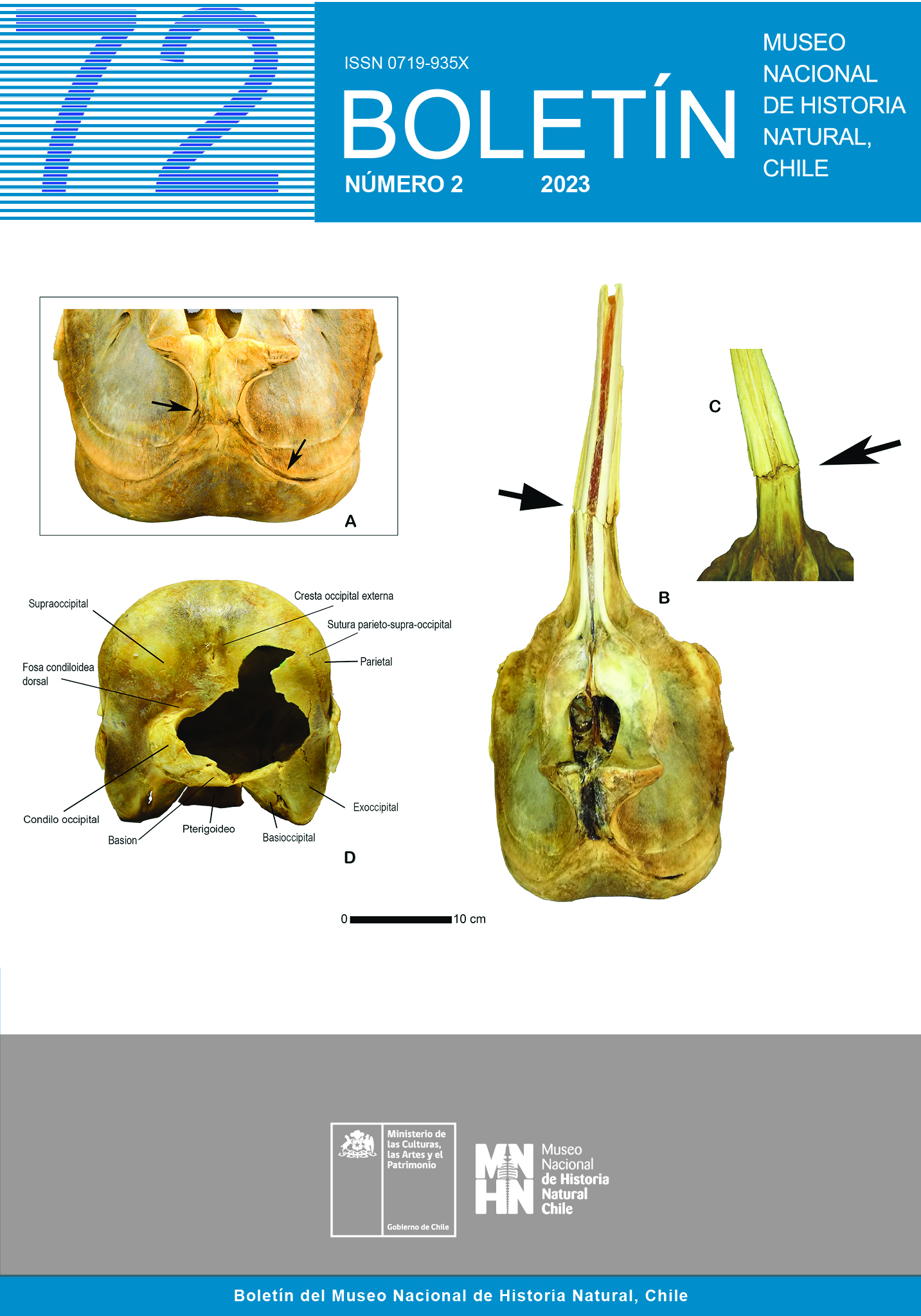

Natural history notes of the Striped Woodpecker (Dryobates lignarius) in central Chile, with emphasis on its breeding biology

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.54830/bmnhn.v72.n2.2023.419Keywords:

Breeding biology, central Chile, Dryobates lignarius, natural history, Picidae, Striped WoodpeckerAbstract

The distribution of the Striped Woodpecker in Chile is from Coquimbo region, prov. Elqui ~ 29˚S, south to the Region de Magallanes, prov. Magallanes, just north of Punta Arenas (53˚S). Its elevational distribution reached up to 2200 m. Its habitat in south central Chile is mainly shrubby areas intermixed with mature trees, such as Peumos, Molles, Boldos, Quillay, Maitén, and Espinos, in drier areas used cactuses, where to nest. In addition, the species can use introduced plants and trees for feeding and nesting. Its breeding season started at the end of September to early December with a peak in October (63.3 %). It is usually single brooded, however, nests found in December are suspected to be a second brood. The nesting cavity seems to be excavated only by the male as no female were seen excavating, and excavation lasted 12 to 15 days. The height from the ground in average was 3.15 m. On average the cavity diameter was 41.9 mm and the depth ranged between 245-300 mm and the internal diameter between 65-70 mm. The cavities were found mainly on dry branches or dry tree trunks, on soft fibers trees or cactuses. The orientation of the cavity opening 45 % was SW, 27 % ENE, 15 % SE and 11 % NE, none received direct light at sunrise and early morning hours. At least three species often attempted to usurp the Woodpecker´s nests namely the House wren, Chilean Swallow and Chilean Flicker. The eggs when fresh were shiny white with a translucent appearance. Its clutch size was between 3 (62.5 %) and 4 (37.5 %) eggs. The incubation period was 13.3 (13-14) days (n = 14). The female incubated 52.91 % of the time (n = 240). They brooded the nestlings for 8-9 days and the female brooded 55 % of the time (n = 170). The nestlings fledged between 27- 32 days. The T10–90 period was 13 days and the growth constant K = 0.337. The average body mass at hatching was 2.8 g and the maximum mass reached by some nestlings was 47 g ~ 115 % of the adult size. The nestling diet seems to be mainly Coleoptera and Lepidoptera larvae and a few soft arboreal spiders. The adults during autumn and early winter ate large quantities of fruits like Molle and Maitén. Also, throughout the season they favor domestic fruits such as medlars, khakis, pears, apples, damascus, and peaches. Its mayor mortality was on the egg stage by failing to hatch, and 84 % of the eggs (n = 56) hatched. Out of 47 nestlings 29.7 % perished and the cause of nestling mortality was by starvation product of nestling competition. In all nests studied minimum one nestling perished by starvation and if there was much allochronic hatching all younger nestlings perished. Nestlings of both genders at fledging time had red feathers on the forehead, in the male get reduced and, on the female disappeared with time. Locally no migration was detected.

Downloads

References

ARAYA, B., G. MILLIE y M. BERNAL. 1986. Guía de Campo de las aves de Chile. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago Chile.

BALDWIN, S.P., H.C. OBERHOLSER, y L.G. WORLEY. 1931. Measurements of birds. Scientific Publications of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. 2:1-165.

BARROS, R. 1921. Aves de la cordillera de Aconcagua. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 25:167-192.

BULLOCK, D.S. 1929. Aves observadas en los alrededores de Angol. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 33:171-211.

CASE, T.J. 1978. On the evolution and adaptative significance of postnatal growth rates in terrestrial vertebrates. Quarterly Review of Biology. 55:243-282.

ESTADES, C.F. 1994. Impacto de la sustitución del bosque natural por plantaciones de Pinus radiata sobre una comunidad de aves en la octava región de Chile. Boletín Chileno de Ornitologia. 1: 8-14.

FIGUEROA, R., R.A. y E.S. CORALES. 2003. Notas sobre la conducta de crianza del Carpintero Bataraz (Picoides lignarius) en el bosque lluvioso templado del sur de Chile. Hornero 18:119-122.

FJELDSÅ, J. y N. KRABBE. 1990. Birds of the high Andes. Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen and Apollo Books, Svendborg, Denmark.

GERMAIN, M.F. 1860. Notes upon the mode and place of nidification of some of the birds of Chili. Proceedings Boston Society of Natural History. 7:308-316.

GOODALL, J.D., A.W. JOHNSON y R.A. PHILIPPI. 1957. Las Aves de Chile su conocimiento y sus costumbres. Platt Establecimientos Gráficos S.A., Buenos Aires, Argentina.

HELLMAYR, C.E. 1932. The Birds of Chile. Field Museum of Natural History. Pub. 308 Zoological Series Vol. XIX, Chicago.

HOUSSE, R. 1945. Las aves de Chile, en su clasificación moderna y costumbres. Ediciones Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

JACKSON, J.A. y H.R. OUELLET. 2002. Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens). in A. Poole y F. Gill (eds). The birds of North America, No 613. The birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA., EE.UU.

JOHNSON, A.W. 1967. The birds of Chile and adjacent regions of Argentina, Bolivia and Peru. Platt Establecimientos Gráficos S. A., Buenos Aires, Argentina.

LANE, A. 1897. Field notes on the birds of Chili. Ibis 39:8-51.

PALMER, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 1. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, EE. UU.

PHILIPPI, R.A. 1964. Catálogo de las aves de Chile con su distribución geográfica. Investigaciones Zoológicas Chilenas. 11:1-179.

RIDGWAY, R. 1890. Scientific results of explorations of the U.S. Fish commission steamer Albatross. No II. Birds collected on the island of Santa Lucia, West Indies, Abrolhos Islands, Brazil and at the Strait of Magellan in 1887-88. Proceedings United States National Museum 12:129-139.

RICKLEFS, R.E. 1976. Growth rates of birds in the humid new world tropics. Ibis 118:179-207.

RICKLEFS, R.E. 1983. Avian postnatal development. Pp. 1-83 in Farner, D.S., J.R. King y K.C. Parkes (eds). Avian Biology. Volume 7 Academic Press, New York, EE.UU.

SHORT, L.L. 1982. Woodpeckers of the World. Delaware Museum of Natural History, Greenville, Delaware. Monograph Series No 4. Weidner Associates, Inc., Cinnaminson, NJ., EE.UU.

SKUTCH, A.F. 1976. Parents birds and their young. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, EE.UU.

SMITHE, F.B. 1975. Naturalist´s Color Guide. American Museum of Natural History, New York, EE.UU.

STARCK, J.M. y R.E. RICKLEFS. 1998. Avian growth rate data set. Pp.381-415 in Starck, J.M. y R.E. Ricklefs (eds). Avian Growth and development, evolution within the altricial-precocial spectrum. Oxford University Press, New York, EE.UU.

VENEGAS, C. y J. JORY. 1979. Guía de campo para las aves de Magallanes. Instituto de la Patagonia, Serie Monografías No 11. Punta Arenas, Magallanes, Chile.

WINKLER, H. y D.A. CHRISTIE. 2002. Family Picidae (Woodpeckers). Pp. 296-555 in del Hoyo, J., A. Elliot, y J. Sargatal (eds). Handbook of the Birds in the World. Vol. 7. Jacamars to Woodpeckers. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, España.

WINKLER, D.W., S.M. BILLERMAN, y I.J. LOVETTE. 2015. Bird families of the World: An invitation to the spectacular diversity of birds. Lynx Editions, Barcelona, España.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Manuel Marin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.